Until recently, when contemplating a future of climate chaos, unaffordable housing, dystopian tech, xenophobic nationalism, and mental health epidemics, millennials at least had one consolation: unlike their parents and grandparents, they didn’t have to worry about nuclear war with Russia. Alas, no more. The recent resumption of atomic sabre-rattling from the Kremlin means a new generation is learning to live with the possibility of sudden vaporisation, which makes this as good a time as any to delve into Oxford’s previous experiences under the shadow of the Bomb. Nowhere is beyond the reach of a nuclear conflict, but here are three sites in the city and its surrounding countryside that were particularly bound up with the atomic arms race.

UKWMO Headquarters, Cowley

If the Cold War had ever turned hot, it is not clear whether Oxford itself would have been the target of a direct nuclear strike. According to the best guesswork of British defence planners in the early 1970s, the city was not among the 106 UK locations expected to be hit in such a conflict.[1] However, similar towns such as Cambridge were on the list, and the actual distribution of the Soviet bombs would have depended on the precise circumstances leading to catastrophe.

In any event, one location in the city was supposed to keep working regardless of whether or not central Oxford was replaced with an atomic fireball. In 1981, part of the former Cowley Barracks was converted into the national headquarters of the United Kingdom Warning and Monitoring Organisation (UKWMO), the body tasked with keeping the official minutes on doomsday. Throughout the Cold War, the government maintained an official policy of ‘civil defence’, insisting that Britain could survive World War Three in reasonable shape provided that various contingency measures were put in place. The UKWMO’s role was to transmit the initial news of an imminent strike (the infamous ‘four-minute warning’), and then use data generated by a nationwide network of Royal Observer Corps bunkers to track the location and magnitude of nuclear explosions, along with the distribution of subsequent radioactive fallout.[2] You can see UKWMO personnel reacting to a fictional nuclear bombardment in a public information broadcast of 1962, in which various tweed-clad extras project an air of sedate sangfroid slightly at odds with the film’s mordant title, The Hole in the Ground. One such ‘hole’ existed on the Cowley site, an ROC bunker serving as the command centre for other observation posts within its regional sector. Whether the post office workers and other volunteers manning it would really have been able to calmly jot down the details of megatons and wind directions as Britain’s cities were incinerated around them remains unknowable.

Indeed, the (so far) mercifully hypothetical nature of atomic exchanges means that many matters are still unclear or shrouded in secrecy, particularly after thirty years in which the issue has been relatively neglected. Along with other civil defence initiatives, the UKWMO was disbanded during the geopolitical lull that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall, and in 1998 the Cowley bunker became the basement storage area for a new student accommodation block at Oxford Brookes.[3] Today, the absence of up-to-date public information is such that several tabloids have resorted to dredging up the fifty-year-old (and now declassified) list of 106 Russian targets as a blueprint for a nuclear escalation of the present Ukrainian war.[4] Oxford’s fate in such a scenario is thus difficult to predict, but if it is hit by Putin’s missiles, this time there will be no-one standing by to record the minutiae of its destruction.

Upper Heyford

The UK’s plans for a Soviet aerial attack encompassed not only defensive measures, but also retaliation in kind. For this strategy, London relied heavily on the senior partner in the NATO alliance, and multiple areas of British countryside became staging grounds for the might of the United States Air Force. One of the most important American strongholds was Upper Heyford, a former RAF airbase located ten miles north of Oxford. Here the long-range bombers of Strategic Air Command patiently awaited orders to take flight for the USSR, backed up by numerous additional aircraft and a town-sized colony of American engineers, support staff, and pilots. At its peak, the site was the largest fighter base in Europe, and although the official US line was always that no nuclear weapons were housed there, the reinforced magazines suitable for storing Mark-17 hydrogen bombs seemed to tell another story.[5]

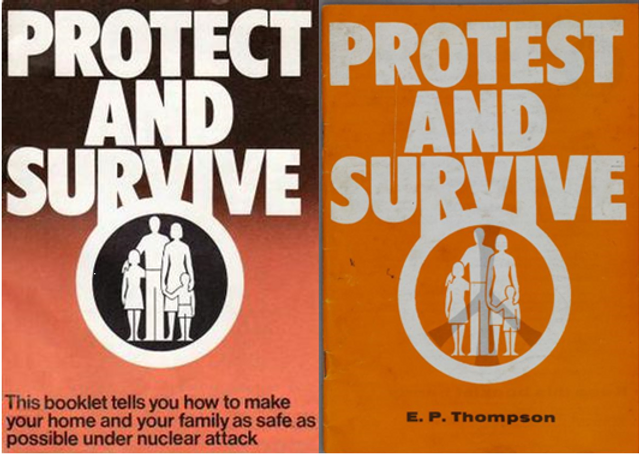

This story was increasingly concerning to many observers, who distrusted the authorities’ claim that civil defence coupled with an ever-more-powerful deterrent was the best means of safeguarding Britain from atomic threats. Responding to a letter from an Oxford professor endorsing this policy, in 1980 historian E.P. Thompson wrote the famous manifesto Protest and Survive, using his trademark deadpan wit to pick apart the letter’s euphemistic reference to the “disagreeable consequences” of a nuclear exchange.[6] Arguing that no amount of preparation could avert total societal collapse in such a war, Thompson then asked university members to “let their dissent be known” about the siting of cruise missiles at Upper Heyford.[7] Answering his call, many students joined mass demonstrations organised by Campaign ATOM (Campaign Against The Oxfordshire Missiles), including a 4,000-strong protest in June 1983. Meanwhile, a permanent ‘peace village’ of the most dedicated activists was established next to the base, where life was an uneasy mixture of mundanity and terror. To while away the time, some protesters played pool with the airmen and carried out minor pranks (such as registering their goat mascot to vote in the 1983 election), yet they were haunted by a constant awareness that this might be ground zero for the end of the world.[8]

Although the protesters did not manage to force the withdrawal of America’s nukes, the collapse of the USSR did the job for them, and in 1993 the USAF pulled out of Upper Heyford. Subsequently, the vast former base became something of a ghost town, and part of the 2013 zombie-apocalypse blockbuster World War Z was filmed on the site. There is a certain queasy irony in a fictional Armageddon playing out on a location that once threatened to genuinely end civilisation, particularly given that many current Oxford students have probably given more thought to how they would react to an undead invasion than to a nuclear attack.[9] That may have to change. Although the Upper Heyford site is no more, there are still US military installations at Croughton and Fairford on the borders of Oxfordshire, and the county also hosts the RAF’s principal airbase at Brize Norton near Witney. Although not on the frontline of the Ukrainian conflict (as one Conservative politician hyperbolically claimed in February), it is very likely that Brize Norton would be central to any major conflict between NATO and Russia.[10] It remains to be seen whether a new generation will react to that prospect with outrage, indifference, or grim resignation.

Harwell

The nuclear arms race was a contest of science as well as military and economic strength, and consequently it was inevitable that Oxford University should play a part. Nonetheless, that role was perhaps smaller than the institution’s reputation might warrant. Although the university’s Rudolf Peierls Centre for Theoretical Physics is named after the man who first grasped the principles behind weaponised fission, he made his key breakthrough (the Frisch-Peierls Memorandum of 1940) long before he transferred to Oxford from the University of Birmingham. Moreover, although Europe’s first nuclear reactor was deliberately sited nearby, the reasons for this were fairly prosaic; Cambridge’s superiority in nuclear physics made it the first pick, but there were no suitable ex-military sites in Cambridgeshire as they were all needed for the defence of England’s east coast. Hence, in 1946 the Atomic Energy Research Establishment was founded at RAF Harwell, some twelve miles south of Oxford.

Just as at Upper Heyford, this formerly sleepy rural site was transformed into a hive of industry, and within a decade over 6,000 workers were employed adding new acronyms (such as GLEEP, BEPO, DIDO, and PLUTO) to Britain’s list of experimental reactors. Although the institute devoted much of its efforts to developing civilian nuclear power, it retained a warlike atmosphere, as documented in verse by one of its senior scientists:

“Foul Harwell, ugliest village of the downs

Where labs and aluminium prefabs sprout

And houses camouflaged in green and brown

Their military architecture shout.”[11]

The institute also pioneered the manufacture of weapons-grade materials for Britain’s own nuclear deterrent, and several of its staff played important roles in the wider Cold War balance of terror. Most infamously, the head of Harwell’s Theoretical Physics division, Klaus Fuchs, was arrested in 1950 for passing technical secrets to Soviet intelligence, including details of his work on the Manhattan Project and more recent hydrogen bomb research. Although historians continue to debate the precise causes and consequences of his actions, he undoubtedly helped to midwife the strategic deadlock underlying the Cold War, and not for nothing did one of his former colleagues call him “the only physicist I know who truly changed history.”[12]

Moral grey areas continue to lurk in Oxford’s scientific hinterland today. Unlike Upper Heyford, Harwell outlived the arms race by diversifying into the private tech sector, and the site has now morphed into the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, a key node in the sprawling landscape of spinouts, start-ups, and public-private research partnerships that orbit loosely around the university. The intersections of academia, finance, and defence policy are invariably murky, and Oxford has recently come under fire for accepting cash from the UK’s Atomic Weapons Establishment to fund some of its physics programmes.[13] Nonetheless, there are some cautious notes of hope amid the gloom. Earlier this year, significant progress toward harnessing nuclear fusion was reported at one of Harwell’s distant successors, the Joint European Torus located at nearby Culham.[14] If developed safely and successfully, this new form of atomic technology could one day provide cheap, clean power worldwide, perhaps lessening our fears not only of climate catastrophe but also of dictators with oil-funded WMD arsenals. As always, science offers humanity visions of a more positive future; let’s hope we can avoid self-destruction for long enough to see it.

Written by Louis Morris

References

[1] Rob Edwards, ‘UK government’s secret list of ‘probable nuclear targets’ in 1970s released’, The Guardian (5 June 2014)

[2] The Home Office, UKWMO (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1979)

[3] Nick Catford, ‘Oxford ROC Group HQ’, Subterranea Britannica (31 May 2001)

[4] Joseph O’Leary, ‘Map of Russian nuclear targets in UK dates back to Cold War’, Fullfact.org (2 March 2022)

[5] Darmon Richter, ‘RAF Upper Heyford: Chasing Ghosts in Rural Oxfordshire’, Exutopia.com (20 August 2015)

[6] E.P. Thompson, Protest and Survive (Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, 1980), p. 12-13, 17.

[7] Thompson, Protest and Survive, p. 27.

[8] ‘Upper Heyford protesters gather 30 years on’, BBC News (5 May 2012)

[9] At least, if the student press is any guide. I have found three articles about a possible zombie apocalypse in the city, and only one posing the question ‘what would you do in a nuclear war?’ Perhaps tellingly, the last of these asks readers what orders they would give to Trident submarines as Prime Minister, rather than how they would try to survive as an ordinary citizen. Jonny Yang, ‘Oxford UK’s least survivable city during zombie apocalypse’, Cherwell (23 January 2021); ‘Oxford on standby for zombie invasion’, The Oxford Student (7 October 2011); James Gibson, ‘Lincoln prepares for zombie attack’, Cherwell (27 May 2010); James Ashworth, ‘OxStu investigates: what would you do in a nuclear war?’, The Oxford Student (29 January 2018)

[10] Henry Goodwin, ‘Tory councillor panned for claiming Boris is ‘on the frontline’ of Ukraine war’, The London Economic (28 February 2022)

[11] Quoted in Harwell: Village for a Thousand Years (Harwell Millennium Book Committee, 1985)

[12] Richard Rhodes, Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb (Simon and Schuster, 1995), p. 259

[13] Ben Jacobs, ‘Oxford University’s ties to nuclear weapons industry revealed’, Cherwell (13 November 2020)

[14] Jonathan Amos, ‘Major breakthrough on nuclear fusion energy’, BBC News (9 February 2022)