Uncomfortable Oxford unequivocally stands in solidarity with the protests and encampments across the world that are calling attention to the horrific violence being perpetuated in Gaza, and we support calls to divest from sources of capital that profit from this conflict.

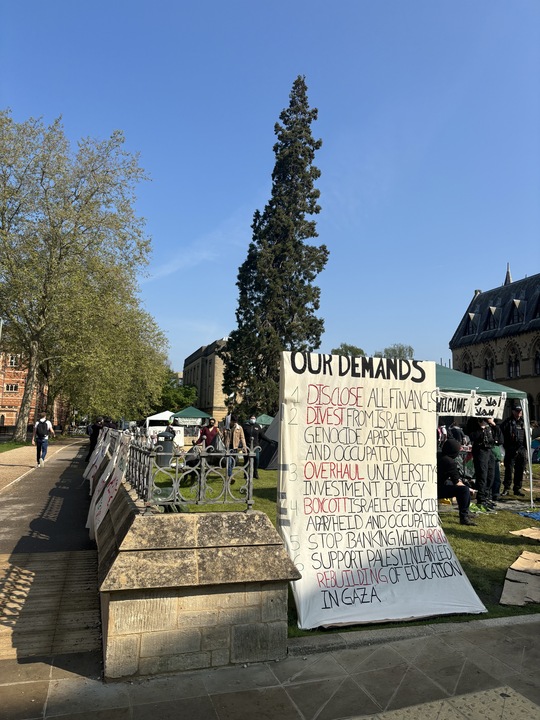

As Oxford students enter the third week of their Gaza solidarity encampment for Palestinian liberation, led by Oxford Action for Palestine in front of the Natural History Museum and the Pitt Rivers Museum (in concert with the University of Cambridge’s solidarity encampment outside of King’s College), I reflect on the rich recent history of student organising at the University of Oxford.

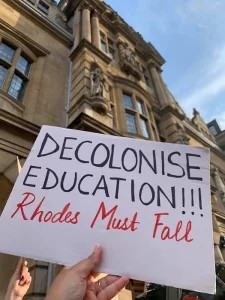

Contemporary student activism at Oxford is not new by any means. The most widespread example is the Rhodes Must Fall Oxford (RMFO) movement, which began in 2015, inspired by the Rhodes Must Fall movement created by Black South African students at the University of Cape Town, South Africa in March of the same year. However, RMFO drew on a longstanding tradition of student protest in Oxford, including action for civil rights inspired by the revolutionary Malcom X’s visit to the Oxford Union in December 1964, three months prior to his assassination. Malcolm X’s visit to Oxford incited student demands for change to the disciplinary proctorial system, which echoed larger civil liberties concerns as students were punished for protesting apartheid.[1] The Oxford Union has a history of inviting ‘controversial’ speakers in the name of free speech, from hosting the former British Union of Fascist leader Oswald Mosley in 1961, a vociferous antisemite and a proponent of ‘racial purity’ to debate apartheid; to just last year in 2023, when its invitation to trans-exclusionary ‘gender critical’ feminist Kathleen Stock resulted in widespread student resistance, including a trans activist who glued themselves to the floor of the Union wearing a t-shirt that said ‘No More Dead Trans Kids’ and a counteraction by Oxford Trans+ Pride, a new coalition established in response to Stock’s visit.

Student protests at Oxford are inevitably covered by major media outlets due to its status in the upper echelons of British society; publications including the BBC, the Independent, the Telegraph, Al Jazeera, and Sky News have all reported on the current encampment. Similar spates of national media coverage occurred in 2015 at the height of the RMFO, whose primary goal was to pressure Oriel College to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes, the notorious British imperialist and blood diamond tycoon, from their High Street building. RMFO experienced a brief resurgence in June 2020 after the global protests against injustice following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police, but the ultimately the statue remains intact today. Dalia Gebrial, one of the student organisers of RMFO, noted that the group’s efforts in Oxford attracted an intense amount of media fervour and interest by the British public, in part due to “Oxford University’s centrality to Britain’s intellectual and cultural identity” that led to RMFO serving as a flashpoint for student activism.[2] Gebrial writes that RMFO brought “the call of decolonisation back to the heart of empire”, where the institution of Oxford University required interventions that went beyond the toppling of Cecil Rhodes’ statue at Oriel College.[3] Patricia Daley, professor of Human Geography of Africa at Oxford, sums up the cultural impact of RMFO: “The fact that a student movement was received so viscerally outside the academy, both nationally and internationally, demonstrates not only the centrality of Oxford to British elite society, but also that the university is very much part of the wider society — not apart from it.”[4]

There has also been a steady increase in sexual violence prevention-based activism at Oxford in recent years. In 2021, Al Jazeera published an investigation titled “Degrees of Abuse” on the rampant sexual violence that occurs in UK universities, with interviews from students at Oxford, Cambridge, Glasgow, and Warwick. The outrage from students was swift, particularly at Balliol College as one of the cases shared in the investigation highlighted Balliol’s lack of response to sexual violence on its campus. In response to the investigation, the group Transforming Silence was formed in late 2021 and hosted a successful symposium in February 2022 addressing sexual violence in UK academia titled “Silence Will Not Protect You” as an homage to Audre Lorde’s famous quote:

“My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you. But for every real word spoken, for every attempt I had ever made to speak those truths for which I am still seeking, I had made contact with other women while we examined the words to fit a world in which we all believed, bridging our differences.”[5]

The group’s demands included prohibiting the use of non-disclosure agreements in cases of sexual violence, changing the University’s legal definition of harassment, the annual publication of the number of complaints on sexual misconduct and violence across the University, and a more robust hiring policy that addresses any candidates’ history of discrimination and if they have or are currently under investigation for cases of sexual misconduct. Similarly, the anti-sexual violence campaign It Happens Here, associated with the Oxford Students’ Union, was launched in 2013 and provides resources for survivors, facilitates consent workshops, and lobbies the university for policy reforms. A major institutional change that recently occurred because of It Happens Here and Transforming Silence’s advocacy is the implementation of a new policy enacted in 2023 that now explicitly prohibits intimate staff-student relationships at Oxford that considers the abuses of power in such situations.

Another recent significant student-led activist movement at Oxford began in early 2020 when the student group Fossil Free St. John’s College began protesting St. Johns’ fossil fuel investments, with the action occurring after Balliol College’s divestment announcement. The group identified the college as having invested £8.1 million pounds in companies including BP, Shell, and British American Tobacco, industries that heavily contribute to the climate crisis. Protestors occupied the college quad for five days, action that garnered solidarity from other Oxford colleges through support motions passed in their respective student common rooms and numerous alumni declaring they would withhold donations until the college divested from fossil fuels. The momentum from the St. John’s occupation led to the University of Oxford agreeing to divest from fossil fuels and commit to a net-zero investment strategy in April 2020, a policy first proposed by the Oxford Climate Justice Campaign. In 2023, activists from Just Stop Oil covered the Radcliffe Camera with orange paint for climate justice. The choice of the Radcliffe Camera, as arguably the University of Oxford’s most iconic building, parallels Oxford Action for Palestine’s choice to encamp in front of the Pitt Rivers Museum, an institution that the Rhodes Must Fall movement called “one of the most violent spaces in Oxford” because of its historic ties to, and display of, colonial and imperial theft.

The current movement for Palestinian liberation at Oxford is not unprecedented. There have been sustained protests against Israeli apartheid and support for Palestinian rights at Oxford both in response and prior to the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people by Israeli forces. The UK ambassador to Israel’s second visit to the Oxford Union in 2023 drew widespread condemnation from groups such as the Oxford Students Palestinian Society and the Oxford Arab Society; protesters also faced racial profiling and threat of arrest for their actions. Violence against supporters of Palestinian liberation at Oxford is ongoing; members of Oxford Action for Palestine (OA4P) were physically attacked on 12 May during their nightly vigil for Gaza by six men. In response, the campaign stated on Instagram: “The incident falls squarely on the shoulders of Prime Minister Sunak, University Administrators, and irresponsible media, who all spent the week weaponizing antisemitism to demonise campus protesters. In a shallow act of desperation, they’ve placed us in danger to distract from the fact that they are aiding and abetting Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza.” On 14 May, the Vice-Chancellor and the university administration issued a series of responses to OA4P’s demands for divestment, disclosure, policy overhaul, and boycotts while rejecting OA4P’s repeated requests to meet. As the campaign stated in its response, this is not enough. If the University of Oxford is to maintain any speck of morality, they must listen to the overwhelming support of Oxford students for the protest and to the over 500 staff and faculty who have signed a letter in solidarity with the encampment, and meet OA4P’s demands in service of Palestinian liberation and an end to genocide.

I conclude this article with a reflection on Professor Priyamvada Gopal’s 2021 essay titled “On Decolonisation and the University” which further speaks to pressing issues of social change in UK universities and the hostile physical and affective environments in which such issues are often received.[6] Gopal, Professor of Postcolonial Studies at the University of Cambridge, analyses the recent calls for decolonisation in the UK in the context of European histories of imperialism and its domination of knowledge production. In her discussion of the Rhodes Must Fall movement, Gopal recognises a key theme prevalent in public discourses about decolonisation: the image of the “over-sensitive” and “woke” student intent on halting debate rather than activists attempting to facilitate a meaningful reckoning over Britain’s imperial past. Sara Ahmed’s 2015 essay titled “Against Students” similarly identifies the consequential portrayal of the “‘problem student’ [as] a constellation of related figures: the consuming student, the censoring student, the over-sensitive student, and the complaining student.” The figure of the coddled student, especially in places of privilege like Oxford and Cambridge, serves as a useful excuse to ignore marginalised students’ real concerns about oppression and social injustice in their educational environment. In response to these claims, Ahmed asserts that “we need to be too sensitive if we are to challenge what is not being addressed … our feminist political hopes rest with over-sensitive students.” I had the privilege of attending Ahmed’s talk on ‘Changing Institutions’ at Oxford last week, which she dedicated to a free Palestine and afterwards, visited the OA4P encampment in solidarity. May we see a free Palestine in our lifetime and liberation for all.

Written by Georgia Lin

For more reflections on earlier waves of protest that affected Oxford, see our articles analysing the specific context and wider historical parallels (stretching back to the seventeenth century) for the Rhodes Must Fall movement. The impact of these and other campaigns are also addressed in our Original Uncomfortable Oxford Tour, which runs twice a week.

References

[1] Stephen Tuck, The night Malcolm X spoke at the Oxford Union: A transatlantic story of antiracial protest (University of California Press 2014).

[2] Brian Kwoba, Roseanne Chantiluke and Athinangamso Nkopo, eds, Rhodes must fall: The struggle to decolonise the racist heart of empire (Zed 2018).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals (Aunt Lute Books 1980).

[6] Priyamvada Gopal, ‘On Decolonisation and the University’ in Textual Practice 35:6 (2021), pp. 873–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2021.1929561