Oxford is known for many things, but neither culinary delicacies nor revolutionary politics generally feature among them. Nonetheless, there is one place where the two have sometimes combined in unusual ways: inside the sticky confines of a jar of marmalade.

Oxford is known for many things, but neither culinary delicacies nor revolutionary politics generally feature among them. Nonetheless, there is one place where the two have sometimes combined in unusual ways: inside the sticky confines of a jar of marmalade.

The city cannot claim to have invented the tangy citrus jam, as its name derives from a centuries-old Portuguese word for quince paste, and even the modern orange version was first popularised in Scotland. Yet Oxford’s nineteenth-century role as the training ground for Imperial elites gave local brands an edge in going global, and this was exploited to the full by one husband-and-wife duo. After Sarah Jane Cooper hit on a winning recipe in 1874, her grocer husband Frank began selling this Oxford Marmalade to the university’s colleges, and “a late-Victorian cult food” (in the words of biographer Brigid Allen) was born.[1] Before long, the spread’s spread had reached literally all continents; a tin was even taken to Antarctica by Robert Scott’s ill-fated polar expedition, where it lasted long past its expected sell-by date before eventually returning to a berth in the town museum.

If it had remained the preserve of well-to-do undergrads and explorers, Oxford Marmalade would have had little relevance to mass politics, but the Coopers’ growing ambitions meant a move to bigger markets and therefore mechanised production. Having outgrown their initial premises at 83-84 High Street, they began manufacturing their marmalade at a purpose-built plant near the station in 1903. This factory was then expanded multiple times, and by the 1930s was employing over one hundred workers, playing a modest part in Oxford’s transition to being an industrial city. This was possible because – despite its Scottish-Iberian origins and upper-class associations – marmalade had become accepted as a favourite food of English workers. Its adoption as a national symbol was neatly epitomised by a quip from expat comedian Bob Hope, who joked “my folks were English. They were too poor to be British. I still have a bit of British in me. In fact, my blood type is solid marmalade.”[2]

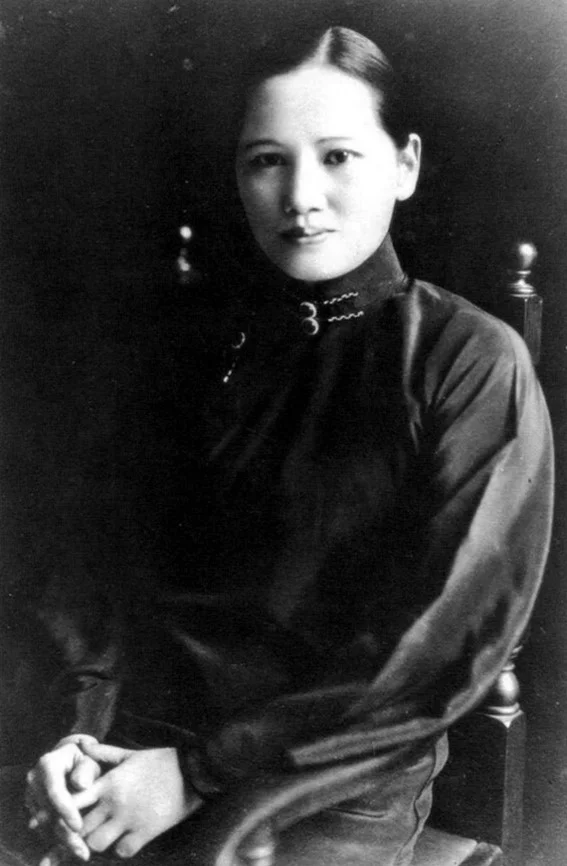

These simultaneous associations with elite culture and mass consumption, Englishness and exoticism, are perhaps what made Oxford Marmalade intriguing for writers during this period. This included those of a distinctively radical bent. Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons books are usually taken as exemplars of outdoorsy traditionalism, but he also witnessed the Russian Revolution first-hand as a journalist in 1917, having befriended the Bolshevik leaders and possibly engaged in some light espionage on their behalf. One of his more intriguing title characters is Missee Lee, a female Chinese pirate, Cambridge alum, and aspiring classicist. Ransome based her on revolutionary leader Rosamond Soong Ching-ling, whom he met in the 1920s and who later became a prominent stateswoman in Maoist China. In the book, Missee Lee’s connection to England is epitomised by her love of the Coopers’ products. “We always eat Oxford Marmalade at Cambridge,” she explains in the course of the story. “Better scholars, better professors at Cambridge but better marmalade at Oxford.”[3]

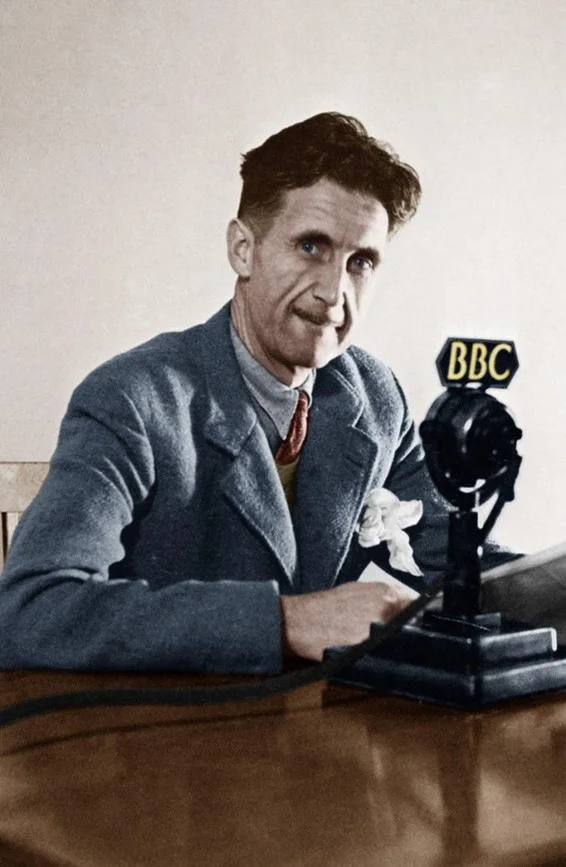

Oxford’s culinary contribution found a still more notable cheerleader in the author and essayist George Orwell. He too has left a complex political legacy, and is best known for the blistering critiques of Soviet communism made in 1984 and Animal Farm. Yet it would be a grave mistake to characterise him as a reactionary; as he himself explained, “every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism.”[4] Some of those lines were about condiments. In his observational account of life in industrial northern England, The Road to Wigan Pier, “the marmalade jar… an unspeakable mass of stickiness and dust” appears as a symbol for the squalor of working-class living conditions.[5] He also listed Oxford Marmalade as a national treasure in his essay In Defence of English Cooking, and even went so far as to provide his own variant recipe to the British Council for publication in 1946. This brief foray into cookery writing was not successful (an annotation from the editor who rejected it reads “BAD RECIPE! – TOO MUCH SUGAR AND WATER”), but his obvious lack of kitchen skills only adds to the mystery of why Orwell wanted to write about Oxford Marmalade in the first place.[6] After all, a commercial food brand hardly seems a natural rallying point for the overthrow of capitalism.

Nonetheless, its appeal to Orwell makes sense in the context of his wider project, which was to reconcile socialism with patriotism in order to protect the former from Marxist dogma and the latter from conservative bigotry.[7] To achieve this, he wanted to guide his countrymen towards a particular way of loving their country, one rooted in affection for the everyday experiences of English life instead of flag-waving jingoism. This comes across most clearly in his essay The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius, in which he wrote “there is something distinctive and recognizable in English civilization… somehow bound up with solid breakfasts and gloomy Sundays, smoky towns and winding roads, green fields and red pillar-boxes. It has a flavour of its own.”[8] Oxford Marmalade, a quirky but familiar element of those stodgy morning meals, matched this flavour nicely. It was a domestic symbol for a domestic revolution, for after all – as he famously put it – “England is a family with the wrong members in control.”[9]

After World War Two, it seemed like this family’s poor relations might finally be gaining a seat at the (breakfast) table. The National Health Service and the welfare state were created as testaments to the power of working-class interests, and in 1966 these interests became ascendant in Oxford when the Labour Party won control of the city for the first time. By this point, however, economic and social changes were already starting to undermine the light industry and relatively homogenous culture which Orwell had viewed as the basis for British socialism. One year later – even as the working-class troubadours of the Beatles revolutionised music with songs about “marmalade skies” – the Cooper corporation moved its production facilities out of Oxford. This formed part of a wider wave of de-industrialisation which was to reshape the city and many others in England.

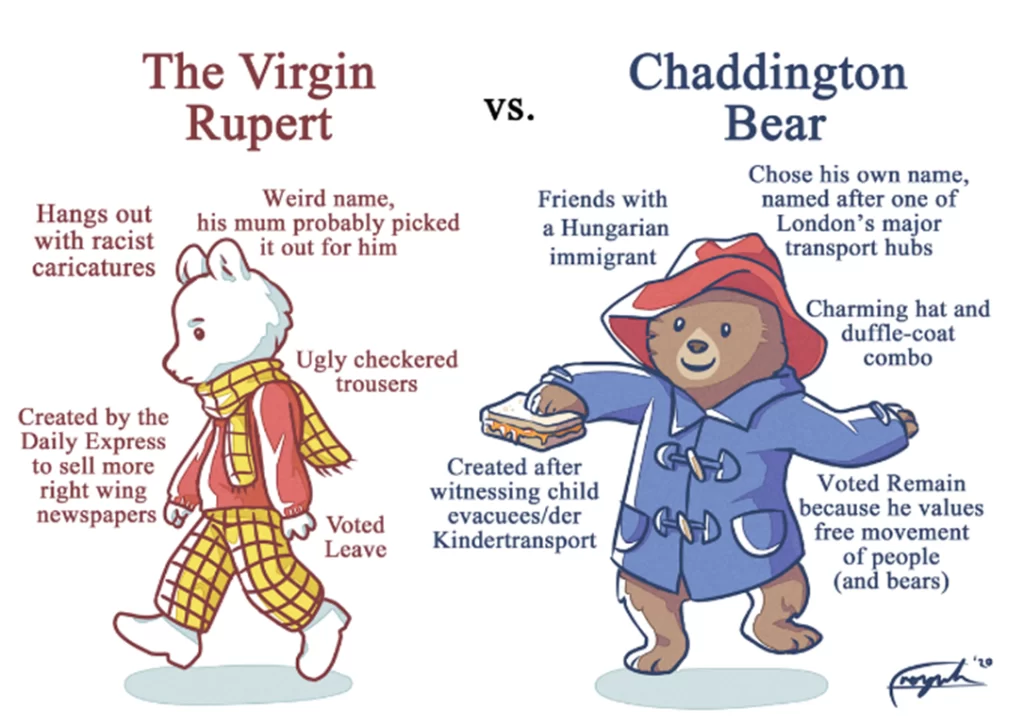

In this fast-changing climate, one fictional bear helped marmalade to become associated with a different kind of progressive cultural politics. After witnessing child refugees during the war, author Michael Bond was inspired to create the character of Paddington, a furry Peruvian immigrant who arrives in England bearing the label “please look after this bear.”[9] In the 1970s, a TV series then entrenched Paddington – and his insatiable appetite for marmalade – as a firm fixture in the national imagination. Since then, he has been increasingly mobilised as a mascot for multicultural Britain and greater tolerance for migrants, particularly following the success of two live-action films during the last decade. In 2010, leading marmalade brand Robertson’s also recruited the character to front their marketing campaign, replacing the ‘Golly doll’ (an offensive caricature of an African man) which had become an unwelcome throwback to the product’s Imperial past.

Marmalade has thus been rebranded as the perfect condiment to accompany liberal cosmopolitanism, but it is not yet clear whether this will be enough to endear it to new generations. Cooper’s, Robertson’s, and the other major historic producer Keiller’s have all been bought up by American food giant Hain Celestial, but the corporation has struggled to reverse a steady decline in consumption; figures from 2017 revealed that 60% of marmalade sales were now made to over-65s, compared with only 1% to under-28s.[10] Oxford Marmalade is clearly no longer a household name, and the former manufacturing plant by the station has been turned into a gentrified restaurant-gallery.

In the end, there is no need to be excessively nostalgic about the fate of Oxford’s flagship foodstuff. Tastes change – both literally and in politics – and Orwell founded his breakfast-table revolution in a form of Englishness that was probably defined too narrowly for long-term survival. Nonetheless, a certain amount of wistfulness about the fading subversive potential of this unassuming spread is perhaps not remiss. After all, marmalade’s defining flavours have always been both sweet and bitter.

Written by Louis Morris.

References

[1] Brigid Allen, “Cooper, Frank (1844–1927), marmalade manufacturer” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004.

[2] “Best of Bob: Some of Bob Hope’s greatest one-liners” in The Guardian, 28 July 2003.

[3] Arthur Ransome, Missee Lee (Puffin 1941) p. 192.

[4] George Orwell, “Why I Write” in Gangrel, Summer 1946. During the Cold War, this sentence was often included in the introduction to American editions of his work, minus its last four words. The Ministry of Truth would have been proud.

[5] George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (Harcourt 1958) p. 15. [originally published 1937].

[6] George Orwell, “In Defence of English Cooking” in Evening Standard, 15 December 1945. See also https://www.britishcouncil.org/research-policy-insight/insight-articles/defence-english-cooking.

[7] Although we should not get too deep into the theoretical weeds and forget that Orwell praised Oxford Marmalade at least partially because he just enjoyed eating it himself. A friend of his described his domestic set-up, including a dining table where invariably there “stood the Cooper’s Oxford marmalade pot. He thought in terms of vintage tea and had the same attitude to bubble and squeak as a Frenchman has to Camembert.”

[8] George Orwell, The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius (1941) https://www.orwellfoundation.com/.

[9] Michael Bond, A Bear Called Paddington (Collins 2003) p. 11. [originally published 1958].

[10] “Marmalade in decline as Paddington struggles to lift sales”, The Guardian, 24 February 2017.