This is a guest post by the Decolonising Florence Park project.

Some street names are engagingly straightforward: The Hill, Station Road, Church Lane etc. They tell a simple story of place and function. Such street names contrast starkly with seven street names in Florence Park. The same neat white letters on black backings distinguishing one road from another, but with far more complex histories leaking out from their uppercase letters.

The seven streets in question are Campbell Road, Lytton Road, Cornwallis Road, Clive Road, Havelock Road, and Clive Road. The men these street names celebrate were all employees who fought for the East India Company, a private company that stripped India of its assets and was the world’s largest opium trader. The men were also key players in British rule in India; a rule that produced 35 million deaths from war and famine. The connection between our community and this inglorious history of invasion and atrocity for private profit both puzzles and troubles us. There is no available historical record of how these names were chosen, but we can assume the choice was intrinsically tied up with beliefs in the greatness of the British Empire, and the white men who led it. That’s the reason why we (Juliet Henderson, Joe Jennings, Caroline Raine, and Judith Secker) started a campaign to decolonise Florence Park street names in late 2020. Our main aim is to contrast the actual local history of the estate with that of the colonialist history symbolised by these men. To do this we are producing materials and holding events that both inform and invite discussion. Some locals object to the idea of changing street names, so we do not feel it is up to us to actually push for this and bring about division in our community.

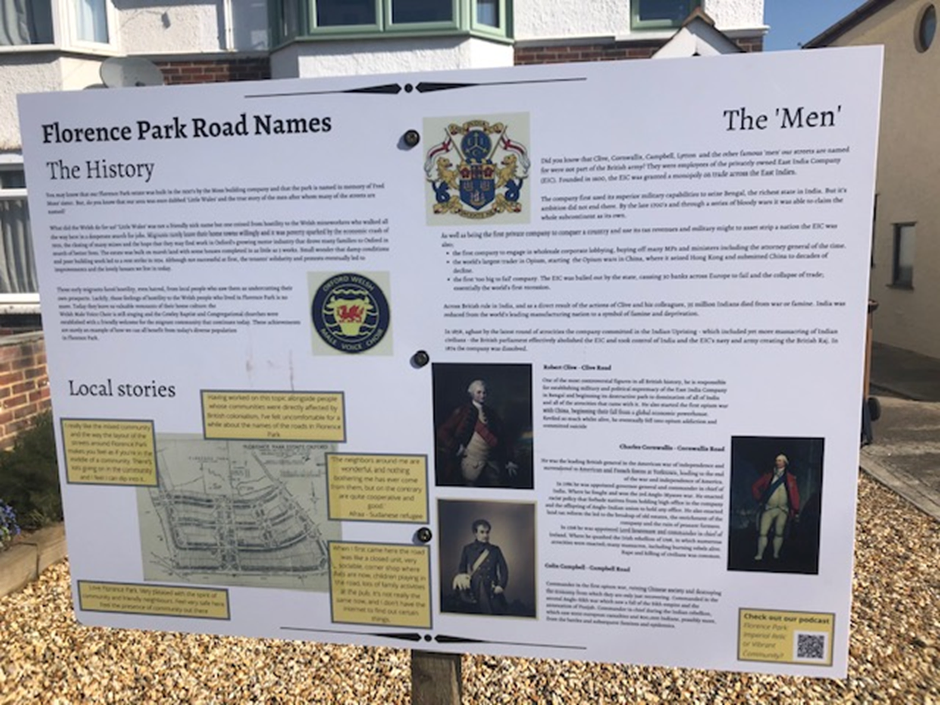

The first step in our project was to produce information boards, now up in many streets, which juxtapose the local history of Florence Park to the violent histories of the men after whom the streets are named. The aim is to differentiate between the horrific colonialist regime embodied by the names on the street signs and the history of local residents fighting for the common good and working for a welcoming community for all. These have generated genuine interest from locals and visitors and positive comments from most who stop to read them.

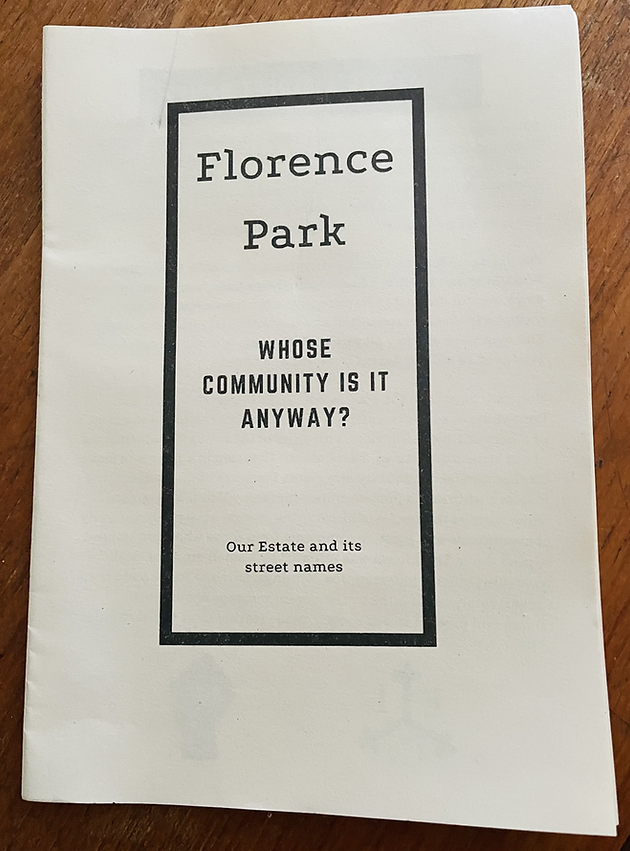

Our second step, taken in August 2021, was to post pamphlets about the project (including information on the local history of Florence Park from the 1930s to the present, as well as details about the East India Company and the men after whom the streets are named) through all residents’ letterboxes. In terms of local history, it explained that it is now nearly a century since the estate was built by Frederick Ernest Moss, a speculative builder who moved to Oxford from Wales in 1929 to build rental housing for men coming to work at the Morris Cowley car factory. Many of the first people on the estate were from South Wales, hit hard by a falling demand for Welsh coal. In parallel, their strongly unionised efforts to reject longer hours and cuts in wages during the nine-day General Strike in 1926 were getting nowhere. As Arthur Exell, one of the Welsh workers at the Cowley car factory, wrote in his autobiography:

“It was the General Strike that had the most effect on me. I was a milkboy then and because of that I was in touch with all the men who were out on strike. My father was a union man and he was one of the first out. He really suffered for that. When the strike was over, he was shut out for nine months. There wasn’t a half-penny of any sort coming in. That was when I learnt what suffering from hunger was. It was terrible.”[1]

Such conditions drove many, like Arthur, to come to places such as Oxford on the Hunger Marches of the inter-war years organised by the National Unemployed Workers Union. Two thousand Welsh people were established here and in other local areas by 1936, which explains why the estate became known as ‘Little Rhondda’ (Rhondda was a coalmining area in South Wales). Whilst not always welcomed by locals, they were a key part of the beginnings of our community and certainly contributed to local Oxford culture with sports matches in the park and a Welsh choir that still exists today.

What conditions did Arthur and others find in Florence Park? In her book, ‘The Changing Faces of Florence Park’, Sheila Tree highlights the fact that although the estate was advertised as “one of the Finest Estates in the South of England” with “seven types to choose from – early application essential”, in reality many of the houses were damp and shoddily built.[2] This led to protests organised by an active minority of tenants and a weekly newsletter ‘The Florence Park Rent Book’ that encouraged a rent strike, called on women to protest, and included these words from one contributor: “For these houses, which are scarcely better than condemned slums, we have to pay rent which is in no case less than 13/6 a week, as well as rates (including the rates for six months before the houses were built), in addition to doing our own repairs.”[3] Whilst they failed to secure a rent reduction, they did manage to get houses improved. The spirit of solidarity and fairness that drove these tenants is still an essential part of our community, and one that contrasts starkly with the colonialist spirit of the men engraved in our street names.

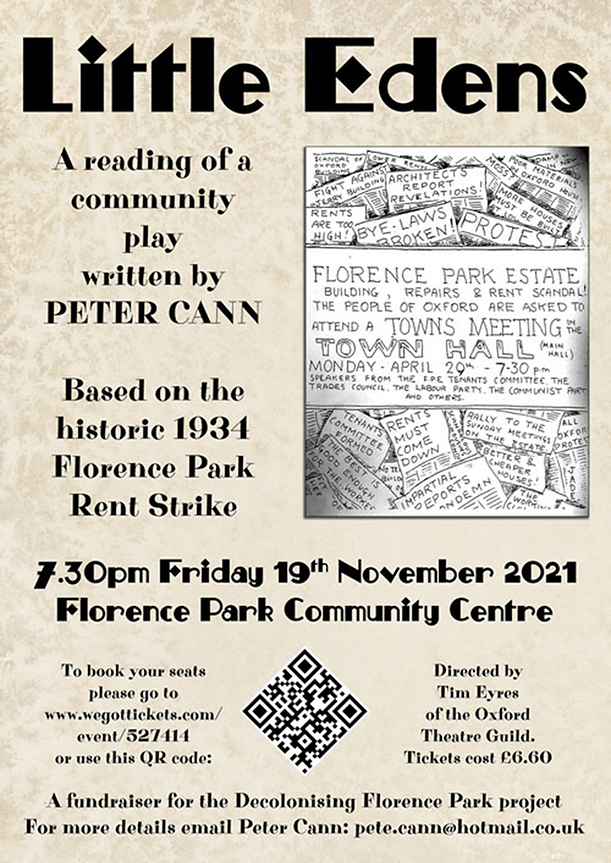

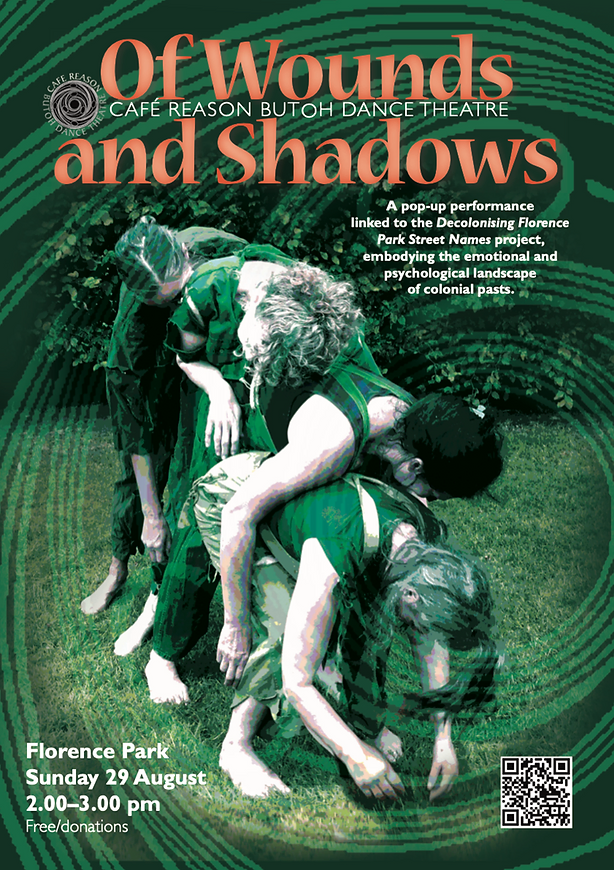

Since delivering these pamphlets we have held three events. The first, in late August 2021, was a talk and Q&A session at Florence Park Community Centre held with Peter Rainey, 95, one of the last living officers who witnessed the end of the British Raj. He joined the Labour Party before being sent out to India and fully endorsed their independent India policy. But, when he served as an officer in the final days of the British Raj, he found his experience there completely at odds with his beliefs. The second, also in late August, was a performance-rehearsal in Florence Park by Café Reason Butoh Dance Theatre, ‘Of Wounds and Shadows’. A pop-up event embodying the emotional and psychological landscapes of colonial pasts. Lastly, in November 2021 there was a reading of a community play by Pete Cann, a local resident, based on the historic 1934 rent strike. Held in Florence Park Community Centre, ‘Little Edens’ attracted a full house and was warmly appreciated.

We still ponder what it might be like if some of the street names reflected Florence Park’s rich cultural heritage. Rhondda Road? Little Wales Close? We are also still keenly aware that the materiality of the street signs is a legacy of colonial rule and plunder that is very much at odds with our present community ethos and spirit. As our Decolonising Florence Park project continues, we now see them as powerful historical artefacts, ones that we can use to remind us of the need to eradicate racism and inequality. They are an ongoing history lesson as we walk our streets.

Written by Juliet Henderson on behalf of Decolonising Florence Park

For more information on the Florence Park rent strike of 1934, see our profile of Abraham Lazarus, one of the leading activists who supported it.

References

[1] Arthur Exell, The Politics of the Production Line: Autobiography of a Car Worker (History Workshop Journal 1981), p. 1

[2] Sheila Tree, The Changing Faces of Florence Park (Robert Boyd 2001), p. 9

[3] James Attlee, Isolarion: A Different Oxford Journey (University of Chiacago Press 2007), pp. 266-7